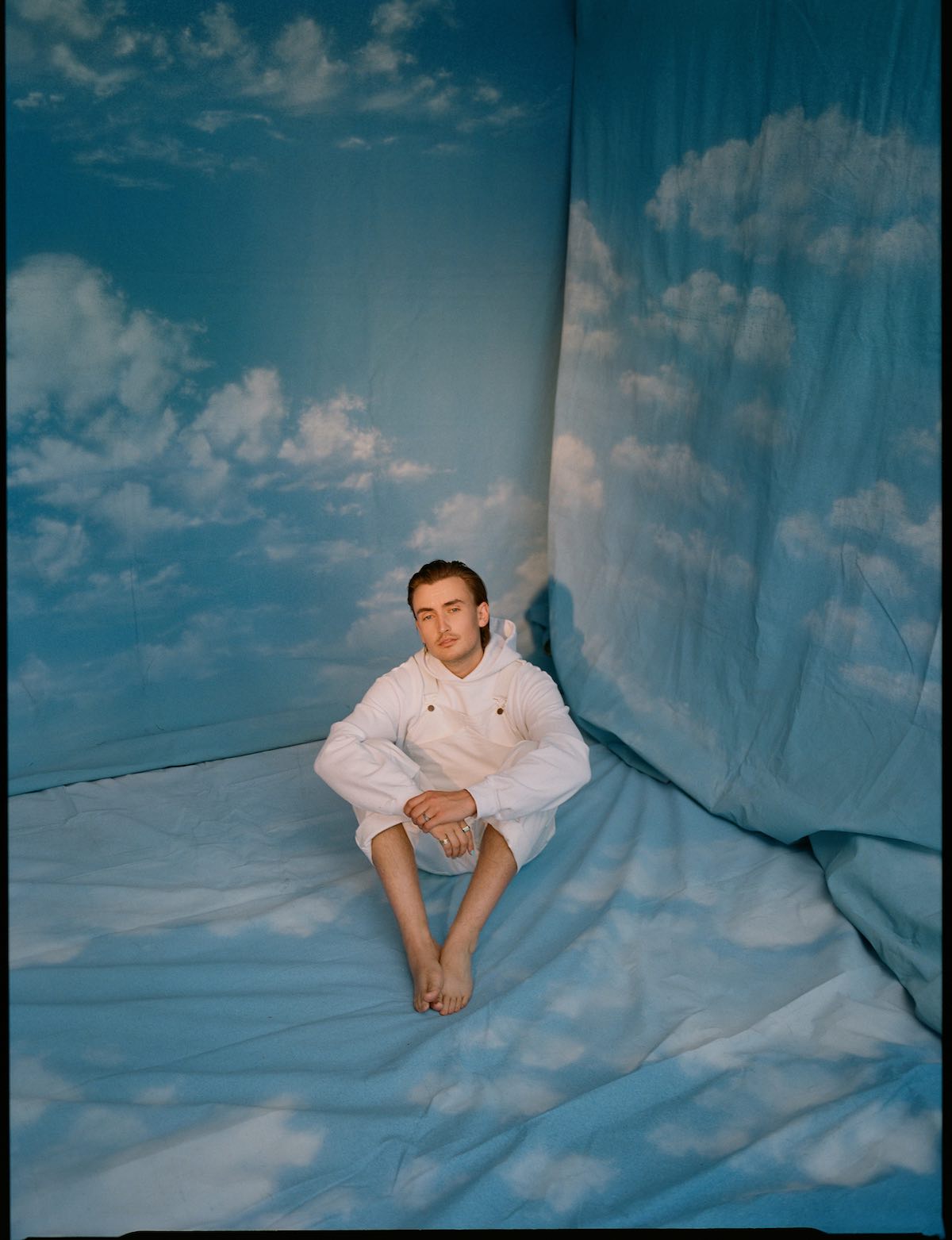

Whether you recognize him as gnash or Garrett Nash, the singer-songwriter recently returned with his second studio album The Art of Letting Go, after releasing a full-length project back in 2019. In addition to his return, gnash discussed a multitude of topics with Variance's Ethan Ijumba talks about his new album, dual-stage names, his independent label, and his adaptations to the state of the music industry.

To further learn more about gnash, be sure to scroll and read the full conversation below.

EI: So for those who know you as Garrett Nash and those who are more familiar with gnash from your early SoundCloud days. Is there any significance on why you decided to use both names in your career, or is it just any personal preference or specifics?

GN: Yeah, so this new body of work, The Art of Letting Go, has been released via both names on Spotify because, at the beginning of last year, we pivoted and changed my stage name to Garrett Nash. Name-brand recognition is something that I took for granted with the gnash projects, and we had done a lot of good leg work even though the pandemic created such a weird divide. So we redirected back and switched back to gnash; nobody was really too bothered by it, which I appreciate. The reason is artistic; this body of work I made is in a very different sonic space and realm than anything I've ever made. I was nervous it wouldn't be embraced the same way I thought if I labeled it as Garrett Nash, then people won't take it as seriously as part of the gnash project. But I found that people are ready to roll with whatever I release; they’re happy with the record, and I'm happy with it. So we double-tagged it to take the pressure off of it as the second Garrett Nash/gnash album because, in many ways, it just feels like a great project that I wanted to have out for me. But, to answer your question, I released it as gnash and Garrett Nash because I really made it for me, and it makes me feel good to see my full name on it.

EI: As for the significance of what the album represents to you, where exactly did the title and emphasis come from?

GN: At the end of the day, The Art Of Letting Go is an album that I made for me, and a lot of the gnash stuff in the past I've made with the understanding of what I think people want from me and this project I made during the pandemic in a time where I didn't know if I would ever even play a show again or if anybody would care about my art when or if it was over or whatever. The album grapples with themes about death and life and where we're all headed, which I was forced to face for the first time in a serious way during that time.

EI: To go along with that, those that haven't and have heard this album, what exactly does it symbolize and reflect when it comes to where you're at right now with this current state of your career and where you are as a person as well?

GN: Yeah, The Art Of Letting Go summarizes the spiritual, emotional, and mental growth journey I've been on over the last 5-6 years since my career started to take off. I got into meditating about a year before the pandemic began, and many of the thoughts and themes on the project are reflections I've had in that space. I've gotten more in touch with my spiritual side over the last couple of years, so the record talks about those things. It talks about my family in a more honest way than I have in the past. It talks about my relationship very transparently, whereas, in the past, I felt that people only wanted to hear break-up songs for me, so I was hesitant about love songs. I wanted to make a body of work to stand by and believe in for a long time.

EI: That being said, at the beginning of your career, you really came in that mid-2010 era of SoundCloud artists that really kind of shaped the way SoundCloud was for those that it was that pit for rappers and upcoming singers such as Marc E. Bassy, mxmtoon, Corbin aka Spooky Black, Call Me Karizma. Your era had its own style where y’all took all these different elements of music such as alternative, hip-hop, indie, etc. It was an eclectic mix of things to make your own sound. How would you say your music has evolved since then?

GN: For the first three EPs, I did a lot of the production myself in my parent's garage. So structurally, the songs have grown a lot, specifically on The Art of Letting Go, even up to my debut album, We. I didn't take into account the musical side for listeners. I was focused on the lyrical side, which is funny because I'm more focused on the musical side now. For example, when I listen to a song, I always ask people what they hear first? Do you listen to the track or the production of the beat, or do you listen to what's going on lyrically? I tend to listen to the production and the whole world of the song and then on the second or third listen. I listen to what they're talking about. I did the opposite because I was very focused on my strong suit, which was the lyrical side of things, and then just doing whatever in the music department.

GN: On this project, I went out of my way to team up with people who I thought could bring a deeper level and greater understanding to the musicality of the project. So I think just on a structural level, my project has grown in the way of just being more musical, and I was playing the songs for the guy who plays keys in my band. He was like, “Oh man, the seventh over ninth on “Palm Trees” is crazy,” and I was like, whatever that means, I have no idea. So I think those first couple of projects were a more raw emotional version of just what it sounds like when I sit alone and make songs. Now, the work has advanced to collaborating with people a lot more, which I'm really proud of. Moving forward, I'm conscientious of that and starting to construct things myself again for the first time in a while, which has been really fun because I think that the more I push outside of my comfort zone, the more I learn.

GN: I didn't think people would like it. So I've always been very conscientious of how lyrics will hit because I've tried it out on Instagram captions or on Twitter in the old days, and this project I went full-send on this feels real to me; this feels honest; I'm gonna go for it. So it's a combination of those two things that have slightly elevated the sound. I'm stoked about that, but I also know that there are people that want the old me, and what's cool about the old me is it's not like it was me and another person or whatever; it was just me by myself, so I can always do that. Every now and then, I pop one of those out; there was a song called “p.s.” on my last record that was very much like my old stuff. So that's kind of the difference, I think, is me by myself versus working with friends.

EI: You mentioned how you worked with friends and collaborated with others and opened yourself to doing more and more collaborations over the years. You've worked with artists such as Max, Clara Mae, and Walk Off The Earth? Is there any artist that really blew you away in terms of working with them that really just had you in awe when it comes down to working with them?

GN: That's a great question, everybody's unique and different, and in the context of this project particularly, I did a lot of it with my buddy Gabe Simon who's in Nashville. He just did all the Noah Kahan stuff and produced a lot of that, and he's incredibly talented. Whenever he came up with an idea or threw something out, I thought it was great. Anikka Bennet was also super involved in this record, and I love what she brought to the table. Then I wrote songs with my dude slim dan, who's got an amazing artist project, and my buddy Grant Averill who's got a thing called “ex-boyfriend” Sam Harris is incredible from X Ambassadors. We wrote the song “Be Here Now” together, and he's really fun to work with for a lot of reasons. One in particular that blows me away with him is that he's created different vocal characters when he does his stacks and layers. When you work with him, he'll hold his nose for one, and I don’t want to give all the secrets away, but he has all these different voices and characters and things that he does. But yeah, I love collaborating with people. Everybody brings something different and unique and cool to the table, and that's the value of collaborating and getting outside of myself for so long.

EI: That said, this album doesn’t feature any main collaborators or features. Was there specific reasoning as to why you approached it in that direction?

GN: We're actually considering re-releasing the Art Of Letting Go with the people I wrote the song with, which is featured on each song because almost everybody on every song has an artist project. I'm starting to work on that where we rebuild the project but bring people in as features, which would be really cool. In the past, with u, me, and us. Anytime someone makes a song with me, I leave them on as a feature instead of trying to replace them. When I got my record deal, there was a lot of conversation about swapping this person out for this person? I have a song called “home” with Johnny Yukon, and there was a lot of conversation about who we could get to do the chorus. And I was like, no, I think we just leave Johnny on it and the same thing with Olivia O’Brien on “i hate you, i love you or,” or whoever I've worked with. I always just leave the person that wrote it on because there's always gonna be that feeling and that emotion that goes with that you can't beat. I'd rather walk with that person to the top than have somebody else do the thing and then try to get up to their level and feel we're not equal.

EI: To further elaborate on your journey, has timing played a big part in the release of this album? Because it was back in 2019 when you released we. Did time play a factor when you were ready to release music again?

GN: Totally, I definitely got shook by the concept of the pandemic because so much of my career has been rooted in touring. I love performing live, and I love people coming to the shows, so The Broken Hearts Club tour was so great in 2019. I didn't know when I would be able to do that again. So that changed the structure of how we approach releases. At the same time, TikTok was taking off, and that felt super overwhelming to me because it felt like another social media I had to master, which sounded like a lot of work and very complicated. So when I finished the record, I didn't know how to release it because everything had changed so much. There was this whole new platform, and I thought the records I had made were only valid on that platform. I'm struggling with this creatively because a lot of songs that I like on that platform are the clips that get stuck in my head. There's no buy-in there, so I'm figuring out how or if I even want to try and play ball in that world. I'll do my best with it. But I definitely made a record focused on its feeling and art rather than the promotional capacity, which is in the past. But to answer your question about the hiatus, it wasn't intentional; time just got away from me like it does everybody. But now I'm like, damn, maybe I don't need to rush on to the next thing, but I'd like to put two or three projects worth of music out this year.

EI: Speaking on the concept of how you chose to release new music, you did separate EPs as a series for each one titled one, two, three, four, and five leading up to The Art of Letting Go. Then you added two bonus songs to the album. Where exactly did the idea of the approach come from? Because the most standard format is 1-2 singles, a music video, and a trailer or some snippets here and there. Where did you get the idea as a series in a different sense?

GN: So when I make a record, I make a lot of songs and try to find a sonic counterpart in the album for the song to create a happy and sad balance. My first record label was called happy sad; it's on all my merch. I have it tattooed; it’s a smiling face with eyes on both sides ):(. So basically, when I make an album, I try to find that happy, sad balance between tracks. So I talked to my A&R about that in June or July of last year, and my A&R Jeff was like, “You know what, we should drop the album in two stacks where you show that.” So, I think a combination of him being like this is a way to get Garrett to put the project out because I was sitting on it for so long, and also a really good idea. So one was about L.A., which was “Seasons” and “Palm Trees.” Then I did two about family: "Money, Love and Death” and “Family, Man.” I did three about love: "Guiding Light” and “I Got A Lot To Lose.” So all of them had a happy song and a sadder song to kind of balance, and that's how I did the two stacks like that.

EI: That makes perfect sense; when looking at it, it was a lot of singles and EPs, but it's more of a build-up, almost like a compilation album.

GN: Which is why we're calling it a project. I want it to feel like something other than my second record, even though, in many ways, I spent more time than I probably will on my second album on this project. Between how I released it and the themes and the sonics nature of the album, it just doesn't feel like the next step in the gnash project; it feels like a whole new step in a new direction. I made about 100 and 80 songs for this album, and we ended up with 12. So there's a bunch of stuff still in the Dropbox that I've sorted into future projects. So then that will be tagged as gnash and Garrett Nash moving forward, and the art will feel similar in the whole thing. It's to a point now where I'm in sessions, and we're writing a part, and the artist sometimes will say, this will be so great for TikTok or whatever. I'm like, great, I love that, that's your medium, awesome. But it's just different from the way that my brain works. I'm not trying to set up a function like that.

EI: With the changes in the industry, adapting to how things are now is a harder change from when you released we in 2019 and now The Art of Letting Go in 2023.

GN: So in 2021, I spent a lot of time developing my TikTok following, and I was getting a bunch of views with videos with over a million views and doing all the trends. I was posting once a day and doing everything I was supposed to be doing. Then I went to Europe and lived life for three weeks. I went to France, walked around, looked at art, and did all these things where I wasn't on my phone. When I came home, I started posting again, and I was getting 100-200 views. They totally crushed my algorithm because I didn't keep playing their game, so after every single I made it a goal for the year that I was, I'm gonna post every day this year, starting January 1st, and I did that all of 2021 until October. It feels good for my ego because you get these little spikes of whatever, but some days feel weird. You could go through a week where you get fewer views, but I was consistently breaking at least over 100,000 views for a long time. I get to a year, time zones change, and things get complicated. I told myself, I'm gonna get off this when I get back to LA; I start posting again. Tanked me, and I was like, you know what? I don't like that.

EI: Which, in terms of the system, is something that you can either play by the rules or not play at all.

GN: Totally, and it plays into all my theories about how like, a lot of the entertainment industry is designed to create cookie retribution systems. A lot of the entertainment industry is designed for the creatives to feel like they have these imaginary goalposts such as, I got in this playlist, or I got this many views on a video. But they only mean something to the building that's been able to market those things and make money off the back end of that creativity. The music industry and TikTok are so tied in together right now. So many labels are obsessed with the concept of virality, which is not actually for the benefit of the creative; it's for the benefit of the business side.

EI: With that being said, what exactly is your focus for Overall Recordings with how you want the artists to be presented and managed?

GN: Our label, Overall Recordings, we're not really worried about going viral. Our goal is to get through that as fast as possible. But it's not ever the end goal of our label. We aim to create the best art, put that on a pedestal, and let everything else happen afterward. For me personally, being signed to a major label, I love Atlantic; we have the most incredible relationship. I see how difficult it is for them to get anything to happen with my records without me having some sort of viral moment. And that's disheartening to me because I'm really proud of these records, and I want to see them work, and I know that they do too. So they're doing everything in their power by boosting the things I post and doing all the little classic marketing tricks. But at the end of the day, it's just a weird time. You have to use social media as a tool and try not to let it run your life and not choose to see virality as the end goal but as the beginning of a conversation. A reason where I can speak from experience with “i hate you i love you.” I had one of the first songs that went from SoundCloud to radio, along with “White Iverson.” I didn't really know what was next when I had this kind of viral thing, and now that moment's happening for people every two weeks. There’s some new thing that everybody's talking about, and it's gotten insane. I love that for those artists, and they get the big record deal, and they go to radio and whatever. Then six months and a year and a half down, they don't have a team, they don't have the infrastructure, they don't have people around them that actually care about them. All the things that I struggled with, and then all of a sudden, you're back at square one and don't know what the point is anymore. So there are two ways to go about it. You know, there's the quick rise, quick demise, and then there's the long and slow; It's a marathon, not a race. The goal with us at the label is to treat it as a marathon, not a race, and when and if something happens, we ride that roller coaster with it.

EI: In a way, how music is now consumed has been a challenge to succeed in the current state that it's in?

GN: Because we've been developing the ground-level work on the way up, the fans are there to catch you when you fall as opposed to being in other people's positions. I've seen pop-offs in the last couple of years who have this massive moment, and they have no fan retention because there's no development there. That's just the nature of the internet, the first video you post just goes crazy, and you're completely unprepared in many ways. At the end of the day, the word viral inherently is an issue because music is not a virus. It is meant to heal, right? Those two things don't work together. Music is healing, and viral is a virus. That is not something in common that I want to see happen; at the end of the day, social media is not social music; it's not supposed to be viral. I could go on and on about all these things we've developed in society: these carrots on a stick for artists to try and get to, to make them feel good and boost their ego because nobody else is doing that for them.

EI: Are there any specific ways to where it can better the current state of the industry?

GN: In the long run, for careers, starting that conversation with a conversation like this is really important because it'll create a sense of camaraderie amongst the creatives who are making the work in music. We don't have a AAA writer's guild. We can't go on strike; we can't all unite and unionize. We would just get shut down, so I think the only way we can make a difference is to have conversations. I often have these very individualized and segmented conversations with artists where people are just bummed and disappointed in the state of everything. Still, nobody knows what to do about it because there's no other answer resolution right now besides we try to go viral, and it works out. The whole industry has shifted to a model dependent upon being viral, but viral once again is not the goal; it's a problem. The best thing that a listener can do if someone's reading this interview is go and seek out music that nobody else is talking about and then tell all your friends about it because that's how you start from the ground floor again, and that can begin a ripple effect in an authentic and organic way.

EI: Are there any specific artists from your label where you’ve seen the organic growth with artists that you have at Overall Recordings?

GN: What we're doing with Daniel Legg, who is signed to Overall Recordings, an incredible talent. Since his name is Daniel Legg, his fans are called the feet, so right now, what we're doing is we're converting people that are on TikTok into becoming The Feet. All of the content is directed towards feet, so if you come across one of his videos that do really well when you go to the comments, it's all the feet. Still, in the feet emoji, it's turning into more of a community thing. Now he's gonna start playing the park shows and invite the feet to come. He's not gonna worry about everybody; he's just focused on his bucket. So rogue shows, basement shows, park shows, living room shows, pop-up shows. We'll bring that back next year and figure out ways to do that because thinking outside the box and determining what correlates to your brand is really important. I'm working with this artist, Juliana Chayayed, who did this cover of “Karma Police” that's been really big that people use in their videos and stuff. She's gonna start doing little shows in Goodwill because a lot of her stuff is about found and lost objects. So we're thinking outside the box and doing these moments, and even if you get kicked out, that becomes the story. Create your buckets, believe in them, and trust that they'll be there to catch you when you fall.

EI: Based on how you’ve seen different eras transition from being about organic music to being geared towards viral moments. What would you say is the best approach for artists to take when making it in the industry?

GN: All the things and some new people will trickle in through the hole, but for the most part, you just trust, develop, and cultivate this community around the music. If you do that, you focus on that and not on going viral, or you do a combination of both. Create content for your fans, and then every now and then, something will work with just music. Make 80 songs; one will work, make 100 videos, and one will go viral. It's that exchange. But a lot of people are putting all the weight into it, which I don't think is sustainable for anybody. I think it's gonna lead to a lot of depression and misery for the creatives who get defeated much earlier before their time comes. They're so focused on expending all this energy on something that isn't the point, the music, the art, and putting that on a pedestal. So that’s my soapbox.

EI: No, that was beautiful. I loved every minute of it. That was like the best TedTalk on why virality and longevity can’t be friends and why you should focus on one, not the other. Now the issue is I think that people can see viral work, but they don't see the long-term effects. You'll see videos of something that works, and then everyone's he fell off, or she fell off after the trend isn’t relevant anymore. I don't want to say all fans are bad or good fans regarding a specific fanbase, and I'm not gonna shame anyone's fan base. Still, I think the general audience and people don’t really know why supporting your artist is important. Don't just play them through YouTube; play them through a different platform, buy their CDS, or sign up for the newsletters and mailing updates.

GN: Yeah, I'm always hesitant about the word should. I try not to say the terms should be supposed to because it creates an unfair expectation of myself or others. But we all could focus more on creativity and the art. We are all very attracted to this shiny concept of going viral and hope that changes our lives and makes everything different. A lot of nights, I go to sleep feeling defeated, feeling like I'm not enough because I didn't have that viral moment that day that changed my life or made my album pop off. But I think that at the end of the day, what brings me comfort is that I create music. People listen to that music, and I love music which is why I put that out in the world, and that makes my soul happy because that's really what life is about. So doing what you love, and figuring out ways to make that happen in the real world, if that helps people, then great. Tell your friends about your new favorite band, music, or album. That’s what demos and mixtapes used to be in communities of music that nobody had ever heard of. Then all of a sudden, you have Sublime or Nirvana that has grown and popped off just because of conversation. So that's my hope, and I'm trying to do it more and more. It's as simple as sending my friends a message saying, “Yo, you haven't heard of this guy? You gotta check this out.” So I think that, hopefully where the focus starts to shift and away from the phones and back to using music as a healing thing and something to create a sense of community.