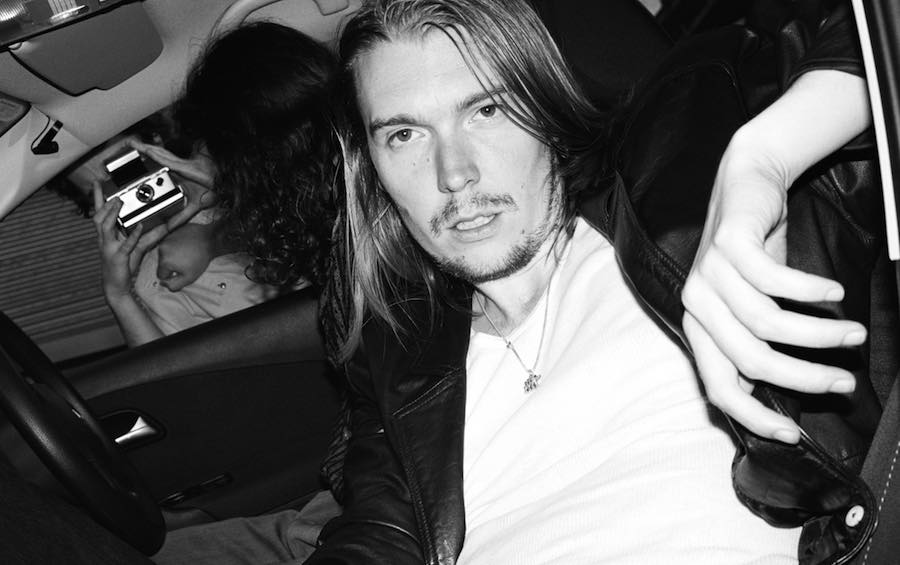

Alex Cameron is one of the acts not to be missed when Treasure Island Music Festival returns after a year’s hiatus to a new Bay Area location, on Oct. 12 and 13. Cameron is one of many Australian names on this non-cookie cutter festival bill, late in the season, that also boasts Lord Huron, A$AP Rocky and Jungle. Other established Aussies include Courtney Barnett, Tame Impala, Pond and Hiatus Kaiyote.

Cameron’s star, however, is fast ascending. His music has been singled out by Henry Rollins, shouted out by Russell Crowe and he was invited to Las Vegas by Brandon Flowers to work on The Killers’ last album.

Forced Witness, his stellar second album, picks up from where Jumping The Shark, his 2013 debut, left off—it’s a continued exploration of the male misfit, in his many unsavory guises. In earlier incarnations, hair slicked back, Cameron wore face make-up to age him and suits like a faded lounge singer, calling to mind Nick Cave. In Forced Witness there’s less artifice; he takes a more heartland stance, in blue jeans and white singlet.

Cameron puts under the microscope the ways these men interact with women; on the internet, in song and the quotidienne. Though he never condones their behavior, he paints intimate portraits of these outre men, warts and all. Like biblical parables, sometimes he offers hope and maybe redemption.

Each song offers a separate vignette and it’s only upon repeated listens that you hear the full extent of the toxic masculinity lurking beneath. “Runnin’ Outta Luck,” “Candy May” and “Studmuffin96” are incredibly catchy, couched in the sheen of ‘80s synth-powered melodies with a good measure of St. Elmo’s Fire-era saxophone solos from “business partner” Roy Molloy.

Sydney-born but now residing in Queens, New York, Cameron took a moment to speak to us from his current home about these misfits, his experience writing with Flowers and acting opposite girlfriend Jemima Kirke (Girls) in his music videos.

Forced Witness is a fantastic piece of storytelling. When and where did you start writing the album?

Thank you. Well, the first song I wrote for this record, I remember I had a blistering hangover like a sweltering cut in half by piano wires or something, and I wrote the lyrics for “Candy May” in about 15 minutes. I just sat on the balcony and scrawled it all out. It came very quickly. I was working full-time in an office; it was a Saturday after a Friday night of heavy drinking. I made this song and I thought, “Shit, I think I have the first song for Forced Witness,” and that all happened in one day, in 2014.

Was that when you decided the office job wasn’t for you?

It was less that the office job wasn’t for me and more that music was.

Sonically, you pull from the ‘80s, which seems a straight-forward, innocent time compared to the chaos we now find ourselves in. Were you actively trying to tackle these larger social ills through the lens of these “micro tragedies” as you’ve called your songs?

I had a lot of conversations with my girlfriend about ensuring the ground that’s covered in what we do is very specific. When you focus on a specific thing, subject matter or theme, it draws people closer to the subject. As opposed to doing something broad, these wide brush strokes catch the masses in this sort of hypnotic, almost fraudulent way. I definitely was inspired by dialogue I was hearing in mainstream media, in politics, especially from men. Because the record is so focused on men; the behavior of men and because I am a man. It’s less about chaos this album—which I do believe is the current state—and more about the way men communicate with women, the way men harbor their emotions in a defensive way to withdraw from being responsible for their actions. In many ways, it’s about manipulation. But primarily, the thing I went with is the way pop music generally uses women—if you’re talking about the way men write songs—as a way of negotiating between men, as oppose to communicating with women. Pop songs are normally about a girl and she has a guy, but it’s about the two guys, not the girl. I just wanted to highlight that bizarre quality.

You’ve mentioned Rick Springfield’s “Jessie’s Girl” as an example. I feel most folks play it straight but you’re a provocateur – you toe the line between playing these distasteful characters for the purpose of storytelling and you take their unctuousness to the limit. We see them, but we’re also rooting for them—there is a humanity to the sleazy guys in “Studmuffin96” and “True Lies.” Is there a danger that people conflate you with these characters?

It’s very rare. I just don’t think I ever want to create art where I have to think, “What if people don’t get it?” I wouldn’t allow for that. When I make something and people confuse me with the character I’m trying to write about, I think that would be a massive failure on my part, and I don’t intend to fail in my art, in my songwriting – that’s just not in the cards for me. It will be my fault if people didn’t get it.

What have you learnt about these misfits as you’ve toured the world singing their stories? And what have you learnt about the world?

I’ve learnt that my instinct was that there’s a lot of beauty, love and good in this world, but there are a lot of villains too. I thought I was writing about an outcast, a person that was uncommon. I wrote these songs in 2015/16, leading up to what has been two years of political revolution; a swing towards the right, a regression as oppose to a progression. I‘ve learnt that a lot of these characters that I’ve written about are more common than I thought. I’ve learnt that there is no way to suppress it; to not think about these things, because if you don’t, you open the art world up to not only censorship, but potentially a disarmament. I don’t want to see my songs soften and become more palatable for the sake of business. I’ve learnt that this kind of writing is required for myself, in terms of reflecting on what I’ve learnt but also the music community. I’m pretty against soft songwriting that doesn’t have a sharp or acute meaning; myself, I find that more difficult to palate.

I feel like in “Marlon Brando” when you’re pissed off ‘cause someone’s called you a faggot, it is the glimpse into the real you.

I grew up with that kind of stuff. People using that phrase to offend straight people; there was a lot of that. Of course, to be offended by that, it means you have to be homophobic, that to be called a gay person is offensive. I personally don’t think it’s offensive but I grew up around a lot of people who did.

What do you mean, “I feel like Marlon Brando circa 1999”?

The character says that, and it shows that he’s coming off the hinges a little bit because he’s confused about who his idol is. If you look at Marlon Brando, what he did and what he stood for, and what he went through towards the end of his life, the character in the song is idolizing someone who was massively flawed, anti-social, not really the icon that everyone adored. That song is all about false idolization, myths and conceptions of who you are, and what you stand for, this person is completely confused and he’s just running off his mouth and digging a bigger hole for himself.

When you were writing these songs, did you have any other songwriter in mind that critiques in this manner? I think of Father John Misty and that line about wanting to be “authentically bogus rather than bogusly authentic.”

I’m completely driven by the songs. I write these songs. And I write stories with different characters in each song. I find myself being more of a narrator. I align myself with each song individually. The song is first to me. I think people have done a really good job of creating this world around the songs – and I really do welcome that. They are all like a little constellation; you can hop from story to story, you can find ties between them, they are episodic almost. I do focus on the quality of the songs rather than how they’ll be perceived.

Is this a particular moment in time where we have seen everything, nothing shocks us, we’re so cynical that this is the only way to engage people?

If I’m ever feeling like there’s a concept behind what I’m doing, [it’s] that I have to stay true to the characters. When you hear a character in one of my songs reflecting and considering that something might be detrimental to them and the people around them, that’s probably me injecting myself in to the song. The characters go much further than I ever would because of who I am. If they ever reel it in slightly, it’s probably me trying to leave a little sense of hope in there, which I wish could be in reality too; maybe someone’s learning a lesson or becoming a better person.

I first heard of Alex Cameron when Russell Crowe showed up on my Twitter feed, with a shout out to “Running Out of Luck.”

Russell just reached out. A friend gave him our CD and he reached out and has become a friend. He is a genuinely sweet person and has offered us a lot of hospitality, taken care of Rob and me.

That was the first time I had seen you dancing. Is that the famous Sydney Strobe? And who invented it, Kirin J Callinan or Alex Cameron?

I thought it was me. Then I made a joke that Kirin did. And Kirin said to me that he actually did. Now I’m confused. But I’m happy to give it to him.

You toured with Brandon Flowers and The Killers earlier this year—and wrote some music together. How did you guys strike up this friendship and working relationship?

I got an email from him randomly, saying, “I like your music.” I had been a long-time admirer of Brandon’s songwriting; I think it’s really powerful. We had something that the other person needed in our own way; we decided to get together for a day. I just wanted to meet him and he was interested in meeting me, I think. We shook hands and then sat down in a studio with a producer and an engineer. I had some ideas that he liked, we were just hanging out, and it went from one day to bringing us out to Las Vegas and spending a month there, writing. And I intend to keep working with him because it’s only so often that you come across someone that you have that ease of creative flow with—that’s what our friendship kind of revolves around, this mutual admiration.

Is it true that you once mistook an email from Henry Rollins for your friend, Henry?

It’s true. I didn’t realize it was Henry Rollins. His email didn’t say Henry Rollins, it just said Henry, I thought it was a friend of mine. When I spoke to Henry, I said, “What a nice radio show, man. I’m glad you played my song.” And he said, “I haven’t got a radio show.” So I ran back home and got my laptop and saw, “Oh my goodness, it’s Henry Rollins!” Isn’t that crazy? And Henry’s been one of my biggest supporters; he helped me get a working visa. He plays my records on his KCRW show. He shouts out to my shows. He’s done as much as someone in his position can do. He’s done a world of good for us. He’s one of the sweetest people that I’ve come across.

You usually hear all the bad stories about the music industry.

Oh yeah, my life can be a living nightmare but there are these specific moments that keep me afloat.

What about your girlfriend Jemima Kirke, she’s in the music videos for “Stranger’s Kiss (featuring Angel Olsen)” and “Studmuffin96.” I feel like this is part of a trilogy, is there a third?

Yes, there’s something coming up. But that’s all I can say.

You guys are electric on screen. What’s it like working with Jemima, is it all business or are you quite loose with scripts?

There’s a lot of improvisation, but when you’re letting someone like Jemima take the lead, it’s kind of like …. something incredibly spellbinding happening. It’s gripping. If you think it’s gripping to watch Jemima, it’s as gripping to play across from her. It’s so free and easy for me to work with her. Whatever “it” is, she has it.

Was it weird when you were shooting “Stranger’s Kiss” that your pictures wound up online with a U.K. paper speculating about your relationship?

It’s not weird being with her. It’s natural. But that was a real wake-up call for me. I just thought we were shooting a video, and the next day, this article came out – it was something that I hadn’t considered at all. I didn’t even know how that stuff works. It was kind of confronting but it also didn’t factor into our lifestyle choices. I’m happier than I’ve ever been; I’m feeling more productive and in love than I’ve ever been. I feel grateful.

So, ultimately, what do you hope your music will do?

I hope that I can pay my rent.

—

TIMF will be held at Middle Harbor Shoreline Park in Oakland, California. For tickets and full details, head here.